Yellow Mountain Road

History

Author: Michael Hardy (source)

The Yellow Mountain Road undoubtedly started out as a game trail. Buffalo, bears, dear and other animals found the path along Roaring Creek to be a great place to cross Roan Mountain. When the Native Americans arrived, they followed the preexisting trails, worn smooth by the passing of a millennia’s worth of hooves.

The trail was obviously found by early explorers. The Spanish from Fort San Juan in present-day Burke County probably used the trail on their way to southwest Virginia in the 1560s. Other explorers, traders and long hunters used the trail to reach the game-rich land in East Tennessee. Then came Samuel Bright in the 1770s. He built a home in the lower part of the county on the North Toe River that became known as the Bright Settlement. Near the confluence of Roaring Creek, he constructed another set of rude shelters. Bright guided travelers along the path to the Watauga Settlement at Sycamore Shoals. The path became known as Bright’s Trace. Later, it was called the old Yellow Mountain Road.

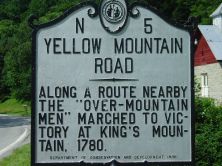

Yellow Mountain Road

Marker ID: N5

Google Map

Nearest Town: Roaring Creek

Date Cast: 1938

It was along this path that Waightstill Avery passed in 1776. According to a story told by his grandson, some Cherokee “came down Roaring Creek to Toe River and crossed… into the North Cove settlement. Col. Waightstill Avery passed up Roaring Creek and, hearing the war-whoop behind, spurred his horse and galloped across from the head of the creek to the Watauga settlement on Doe River. When he returned… he ascertained from a woman, who had been a prisoner, that several braves followed him for some distance and desisted only because they suspected that he was trying to lead them into an ambuscade.”

The road’s most famous brush with history came in 1780. The Overmountain Men, coming from the Watauga Settlement, crossed Yellow Mountain and headed down the creek on the Yellow Mountain Road. They were on their way to fight against the British and Loyalist forces at Kings Mountain. The battle was an overwhelming Patriot victory. Thomas Jefferson wrote that the battle of King’s Mountain was the turning point of the American Revolution.

In June 1864, George W. Kirk’s Unionist raiders used the route over the mountain and down Roaring Creek as they moved toward Camp Vance near Morganton. At some point, they split off from the original road, and took a path through the Hughes, Crossnore, Pineola, and Jonas Ridge area. According to many local stories, Kirk’s men took the “Winding Stairs” road down the mountain. However, just about every road coming up the mountain was called the “Winding Stairs.”

In the 1920s, portions of the Old Yellow Mountain Road were paved. Instead of traveling up Roaring Creek, the direction of the road was changed. Now motorists and their increasingly plentiful automobiles could travel between Spruce Pine and Cranberry, and on to Elk Park and Tennessee.

Today, traces of the old route can still be found. There is a section of the old sunken roadbed behind the Sunnybrook Store. On up Roaring Creek, visitors can leave their cars and can mingle their footprints with those of thousands of others who trod this path on their way to a new life in the Watauga Settlement or to raid Camp Vance. Maybe through the forest foliage we can still hear the buffalo, elk, and deer that once used the trail to access water.

Original Source:

Michael Hardy. “The Famous Yellow Mountain Road.” The Avery Journal-Times, https://www.averyjournal.com/, 16 May 2018, https://www.averyjournal.com/avery/the-famous-yellow-mountain-road/article_4257c142-8dac-578f-b739-77511093b3cb.html.

Marker Text

N5 – Yellow Mountain Road

Along a route nearby the “Over-Mountain Men” marched to victory at King’s Mountain, 1780.

Essay

The Yellow Mountain Road that stretches through what is today Avery County is part of the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail. In the fall of 1780 an army of backcountry men left western Virginia and marched towards what would become the Battle of Kings Mountain. The troops were given the nickname of the “Over Mountain Men” or “Back Water Men.” The term “Over Mountain Men” has been used to describe other groups of patriots during this time, but it mostly represents the Appalachia men who crossed through the backcountry regions of Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and South Carolina on their way to Kings Mountain. The majority of these men were of Scotch-Irish decent and had settled in the backcountry regions in the mid-1700s.

The group was comprised of men led by Colonel Isaac Shelby from Sullivan County in present-day Tennessee; Colonel William Campbell from Washington County, Virginia; Charles McDowell with men from Wilkes and Rutherford counties, North Carolina; and John Sevier, also of Sullivan County. All of the groups of militiamen met along the Watauga River on September 25. They took the only roadway that connected the backwater counties to the eastern side of the Blue Ridge Mountains. They left Sycamore Flats and went through Gap Creek Mountain to the Toe River then headed south to the top of the mountain at Roan High Knob and Big Yellow Mountain. On a 100-acre tract of flat land the troops were paraded to see how they were fairing on the journey. At this point (the site of the marker) they had hiked approximately twenty-six miles.

Along the way they stopped at Roan Mountain to rest. By the end of this first day the men had hiked up and over the mountain before making camp on their way down the mountain. There the troops separated at Gillespie Gap. Some men followed Colonel Campbell and headed south towards Turkey Cove, while the other troops crossed the Linville Mountains and spent the night at the home of Colonel Charles McDowell. The militiamen then went on to form a coalition of approximately 1,000 troops to fight and defeat the British Army on October 7th at the Battle of Kings Mountain.

Two hundred years after the first march during the Revolution, the United States Congress established the Yellow Mountain Road as a national historic trail. In 1975 the first march took place over portions of the original trail and the Overmountain Victory Trail Association has continued the tradition ever since.

References:

- Lyman C. Draper, Kings Mountain and its Heroes (1881)

- Henry B. Carrington, Eyewitness Accounts of the American Revolution, 1775-1781 (1877)

- Robert Collins, The Over Mountain Men March Again (1979)

- Over Mountain Victory National Trail: http://www.nps.gov/ovvi/